I personally agreed most with the Romantic movement. Their focus on Beauty and Art, as well their insistence on the primordiality of subjective experience resonated more than the cold and dry Enlightenment principles. Furthermore, I think that Romanticism sprung up precisely because of a distrust of Reason, a distrust with which I am sympathetic. Modern science and analytic philosophy are the progeny of the Enlightenment–fully realized versions of what were new and young principles in the time period we were reading. Contemporary society thus has the pitfalls of the Enlightenment to the extreme as a consequence of this–and Goethe and Schiller’s critiques seem all the more relevant.

Learning about the Enlightenment and Romanticism I feel has given me an even clearer view of today’s society. As I argued above, because I think that today’s society is in many ways approaching the logical extreme of the Enlightenment (and in some ways perhaps not), I think that reading thinkers from both movements helps understand our current situation in a deeper manner–the positives, negatives, problems, solutions, values, etc.

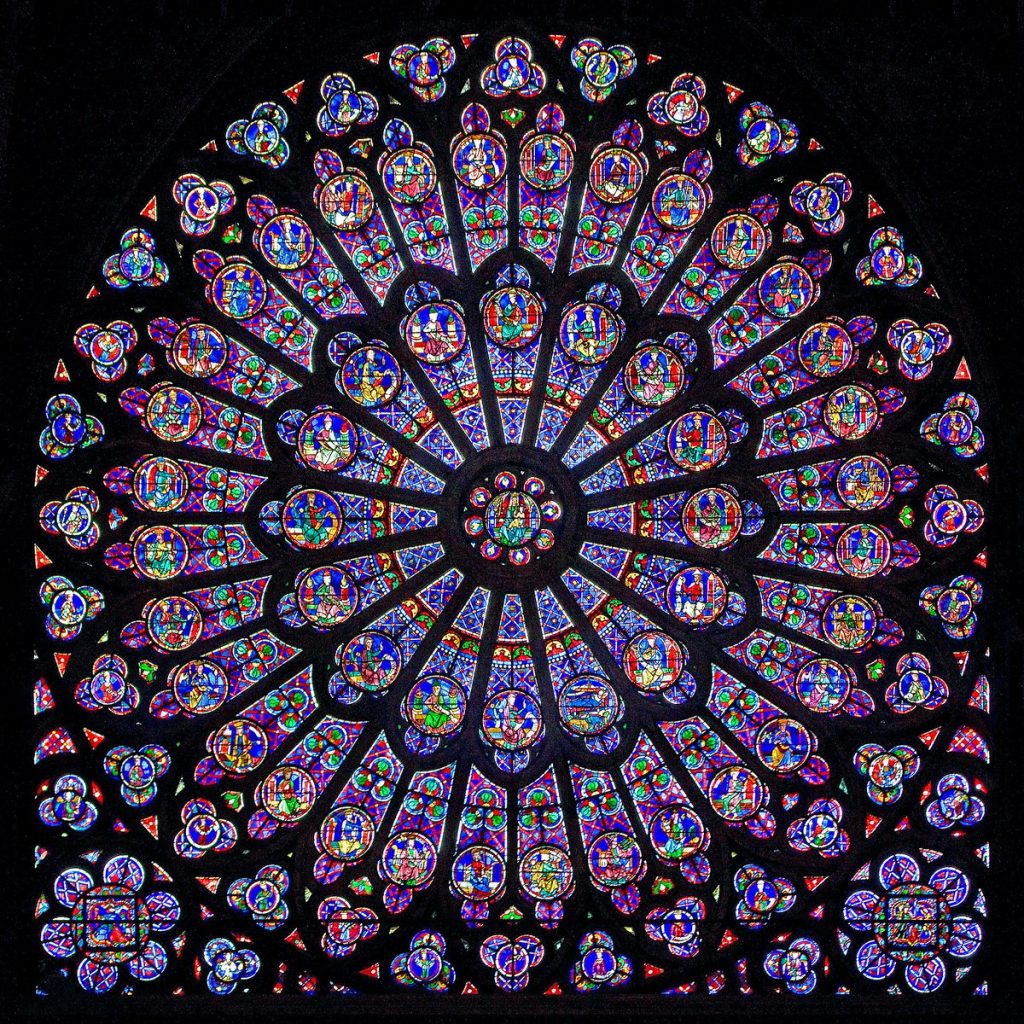

I think that the most important takeaway from this class is the idea that art and science are not mutually exclusive. It is often times an assumption that science walks a path that is both methodologically and analytically distinct from art. I think that Professor Watkins has done a good job at arguing that this is an irrational position (i.e. by citing studies indicating that doctors who look at artwork tend to treat patients more accurately and better). Decreased attention to the Humanities (in particular, philosophy, art, and literature) is to our peril. And while the Enlightenment provides us with many important tools, the importance of recognizing its limitations and its negative consequences were relayed very effectively in this course.

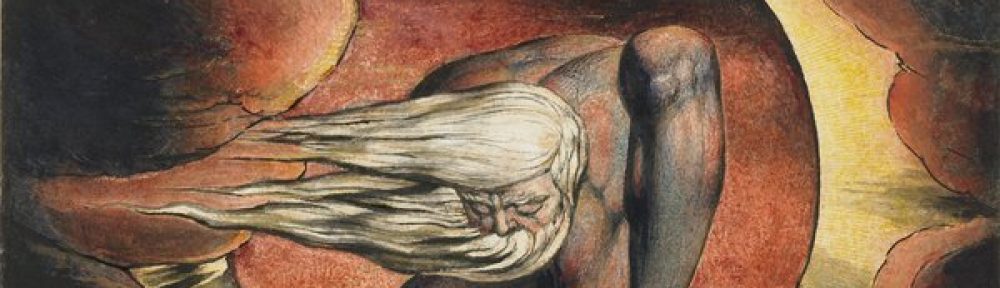

The picture, “A Moonlight with a Lighthouse, Coast of Tuscany” painted by Joseph Wright, is meant to capture the Romantic skepticism of the Enlightenment’s Reason.