by Charizart

A collection of snacks and candies I grew up with as a Filipino kid in America

by Charizart

A collection of snacks and candies I grew up with as a Filipino kid in America

A brief monologue involving names, expectations, and the irony that can come from putting them in the same room and forcing them to talk.

When I was born, my parents had the forethought to prepare two names to choose from. Being born as a girl meant that the name Victoria was what stuck around, but if I had been a boy, it could have easily have been Nicholas. The reasoning behind choosing the names is about as expected as it could be, for a baby name; both were names that my parents enjoyed, and both owe their meanings to the word “victory” if only to slightly different contexts. It was a meaning they had wanted to give me, in the hopes that I would be a “victorious person” in this life. To this day, I still can’t say how much of it actually worked—I always believe it to be something I’ll only finally learn through hindsight—but I have a feeling that it will all catch up with me sometime later. Because in the end, what’s in a name?

Quite a few things, in fact. And even more, when you’ve been given more than one.

And that’s the thing here: I have a second name. An entire name, given to me after one fateful meeting with the monks when I was still an infant. One with a meaning chosen to help balance the qualities I already had, with the ones I lacked. They said I was too cold, laid up with too many chances to be isolated and alone as I grew up. Not enough fire, not enough passion. So they gave it to me, when they gave me the name Fèngyìng, using the characters 鳯 (lit. [male] phoenix, firebird) and 映 (lit. to reflect [light], to shine) to spell it. A decent name with a straight meaning and in many ways, very indicative of the person it belongs to. At least, in a symbolic sense.

There’s a certain significance in a name. Names have power. Names are power. And having two doesn’t change that fact. I’d even go as far as to say that, to some extent, it could even become a problem. It doesn’t change the fact that I have it, but neither does that change the fact that I believe in its influence and I intend to live with that in mind.

But if I’m being honest, my mother seemed to have different intentions in mind when she was raising the younger me. I was taught the virtue of respecting my elders, growing up. To be good by and to my parents; to take care of them and engage in good conduct (the kind that brings a good name to the family) amongst other things. And it’s far from an uncommon lesson—within the Asian-American community, the lessons of filial piety are hardly ever not seen, and the expectations of following such a thing are even stronger back in the East than they are here in the United States. And it’s even more difficult to ignore it when the roof over your head belongs to the people who have been teaching you this mindset your whole life, because that’s just the way they know life to be.

Case in point, the classic “How are you going to act when you have a family to take care of too?” question, and all of its lovely variations.

See, the thing about filial piety is that you’re expected to do as your family expects of you. For sons, it’s to carry on the family legacy by passing down the family name to the next generation. For daughters, much of the core remains the same; to bring the family honor through a family of their own. But with the rise of the most recent generation trends, that expectation becomes difficult to meet. The practice of raising a family upon entering adulthood has become more of an ideal than a reality, but it’s also the result of the shifting dynamics in today’s society.

It’s enough to make me wonder why my mother still holds onto the expectation, and why she acts as if she expects me to allow her to make my choices for me.

Maybe it’s a need to cling to the familiarity of the past, or some innate desire to control what isn’t entirely understood. Maybe it’s something entirely different from what I think it to be. But despite the uncertainty, I find that to be the least of my worries, because my expectations for her lean in a different direction; Why?

Why does she still hold all these expectations? Why does she expect me to follow them? Why doesn’t she consider the possibility that I may not want the same things for my life that she does? Why did she choose my name and its meaning, when nothing in life has guaranteed that it will work in her favor the way she may have expected it to? Why won’t she listen to the things I’m trying to say?

These questions and more—they’re what I often find myself wondering in the aftermath of our arguments. Sometimes things work out, and we compromise. Most times, we continue to clash until we’re at each other’s throats. In hindsight, it’s an unhealthy relationship. In practice, it’s a vicious exchange. I can only imagine how things will continue to escalate in the future, if we continue down this path.

But hopefully one day, it’ll get better. After all, if it takes losing the battle to win the war, I know which victory I would rather enjoy.

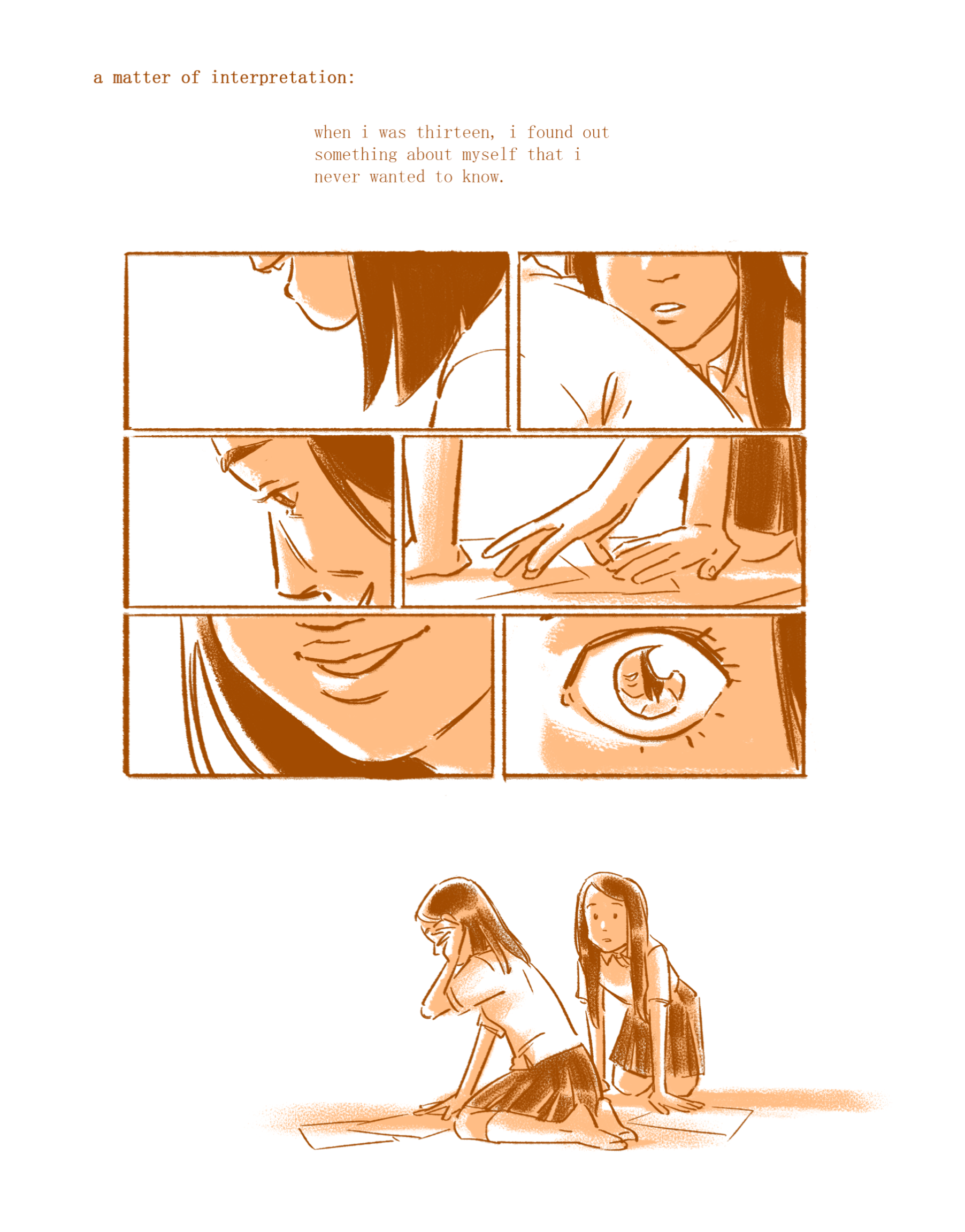

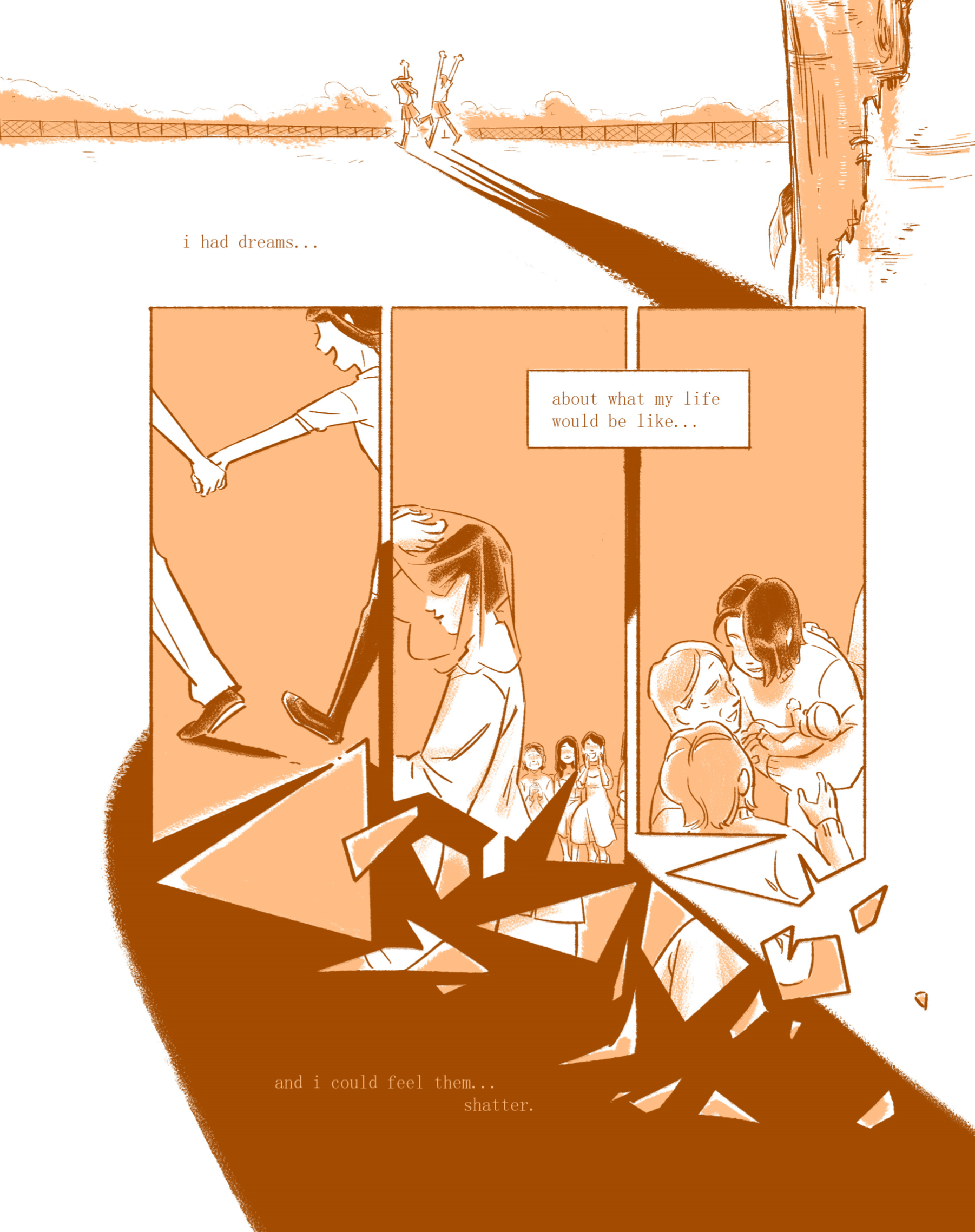

by Al K. Teng

A 4-page comic on managing the intersection of cultural heritage, family, queerness, and personal freedom.

by Kienna Shaw

一 (jat1, yut; one)

I don’t remember when my grandmother started teaching me Cantonese. But first thing every morning I stayed with her, when I would wake up to the smell of blueberry pancakes and perfumed hand cream in her small apartment, she would greet me.

“Zou san. Good morning.”

I’d repeat after her, sleep-tied tongue tripping over the intonations. Gently, she’d repeat it again and I would respond again, a morning ritual of call and response until the words settled in my mouth again. And she would smile, serve me a plate of blueberry pancakes, and we would have our quiet morning together.

二 (ji6, yee; two)

Second generation Chinese-Canadian, two generations of removal from speaking Cantonese.

My grandmother raised my dad and aunts and uncles in a mining town in Northern Ontario, one of two Chinese families in the entire area. Even if it wasn’t written into the law, English was the language that was demanded of them.

It was the same in the large cities that my dad and grandmother eventually moved to, even the ones that boasted of being multicultural. And so I grew up with English as my first language, and Cantonese was never really my second.

三 (saam1/saam3, sam; three)

My grandmother never spoke much about her life back in China. I can only remember three times that she ever told me stories of her sisters and her mother, of their life before and during the war. Always in fragments or in passing, she seemed to focus on the stories of my aunts and uncles and cousins before she ever told her own.

Studies have shown that our memories are tied to the language that we experienced them. Sometimes I wonder how many stories she could have told in her own words, her mother tongue, that I never got to learn about because I didn’t know the right words to understand them.

四 (sei3, say; four)

“Four is unlucky,” my grandmother told me one day while I was practicing my numbers. “It sounds like the word for death.”

The same way that intonations flowed from character to character, so did the small lessons of traditions and culture flowed from the words. From learning how to say Gung hei fat choi, I learned what to eat on New Year’s for long life and fortune and how to avoid sweeping out the good luck. From learning how to say lai-see, I learned the significance of the colour red and familial connections and structure.

Like the Cantonese words merging into my vocabulary, the Chinese traditions merged with my Canadian life. My words weren’t fluent and my understanding of the traditions were never truly traditional, but they were my family’s.

And every time I saw that an apartment building didn’t have a fourth or thirteenth floor, I would smile because I knew why.

五 (ng5, mm; five)

Food became a way to share traditions. Within each dish is a story of recipes passed through generations and an expression of love. These dishes and ingredients with their Cantonese names became the food that I shared with my family at the dining room table.

Even now there are foods that I don’t have English words for because the Cantonese names are so integral to what they are. I may not be able to read the menu at a Chinese restaurant, but I can safely order five different menu items in the only words I know how to.

六 (luk6, look; six)

“But you’re not really Chinese.”

I was six the first time I heard someone challenge my identity, and it was certainly not the last. It confused me why someone would, especially when they knew my family was Chinese.

They always listed the same reasons. I was second-generation, I didn’t have the same values, I wasn’t fluent in Cantonese. Each time it felt like it was an affront to the things that my grandmother had carefully passed down to me, the family traditions and heritage that were tied to the few words I knew. But I don’t know how to explain the importance of a language that wasn’t my mother tongue, and so I stayed quiet.

七 (cat1, chut; seven)

When ALS slowly took away my grandmother’s strength, one of the first things to go was her ability to speak. The small language lessons became mine to teach as I helped her learn sign language so that she would still be able to communicate with us. We used seven signs the most.

Yes. No. Hungry. Thirsty. Full. Thank you. I love you.

And when it was my turn to teach her the numbers, I went through them in sign language and Cantonese. Yut, yee, sam, say…

八 (baat3, baht; eight)

She passed away in the spring, a few months after her 80th birthday. Eight is supposed to be a lucky number, sounding similar to the word for good fortune. The irony felt heavy on my tongue when I remembered that lesson and muttered it under my breath.

For a moment I looked over to see if my grandmother had heard, if she would be proud of me for remembering. Although I hadn’t heard her voice or had a lesson in such a long time, it was only then that everything felt so quiet.

九 (gau2, gow; nine)

Over the years, my other relatives tried to teach me small bits and pieces of Cantonese, but it never felt right.

Eventually, I only used the words for the traditions and the foods when I didn’t know the English word.

Nine years later, I’m in university, giving my friends chocolate coin lai-see and having a small potluck of secreted snacks and mooncakes. It’s close to midnight in the residence dining hall and we’re having a lively discussion about traditions and food, about being Asian diaspora. In a moment of quiet, my friend turned to me.

“How do you say good morning in Canto?”

For a moment I smelled blueberry pancakes and perfumed hand-cream. Then I smiled, and with my grandmother’s voice guiding me, I spoke.

十 (sap6, sup; ten)

It’s been just over ten years since my grandmother passed away. Every few months, we visit where her ashes are scattered and we bow three times in front of her nameplate. As I stand between the trees and I look up to the skies, I think about all of the small things she taught me, woven into those language lessons.

Cantonese will never be my mother tongue. I accepted that fact before I even truly understood what it meant. But the word for mother and the word for paternal grandmother are only one intonation away from each other, so perhaps it’s my grandmother tongue.

It’s the language of the history and the heritage.

It’s the language of the food and the traditions.

It’s the language of my grandmother’s story and mine.

by Sofie-An Nguyen

I don’t think I have ever seen artwork of an Asian person who wasn’t a traditional or historical figure, like a geisha or the buddha. To add something that I believed was currently missing from this collection, I settled on creating a portrait of something–or rather, someone– I had never seen in visual art: an Asian child. Surrounded by foliage, this nameless child of ambiguous Asian descent stands alone. Wearing a baggy sweatshirt and sporting long locks of straight black hair, she looks off to the side at whatever has caught her attention. Relaxed, she simply turns her head and forms the slightest of facial expressions, as if to ask, “What are you doing here?” or “Who are you?” As viewers look on, they will never know what she is glancing at, but the gleam in her eyes compels them to wonder. I used charcoal, a messy medium of blacks, whites, and grays, to create a stark contrast between this character and her environment. As I worked, the color and intensity of the sticks smeared, faded, and smudged in the progression of the piece. In the end, she is the center of our focus.

中秋快乐

There is a full moon tonight. When we were children, we would light lanterns.

There is a legend that goes with this tradition, though depending on who you ask, it changes. There are some that say the lady in the moon was selfish, that she drank the potion of immortality and was banished. There are others that say she loved her husband and drank the poison to spare him, and as a reward for her love, she did not die but was sent to the moon instead.

Those are just two – there are many variations.

(I forget which one I heard first; I think like the one where she is in love the most)

The lanterns are lit – if I remember correctly – so that she may find her way home.

There is no place in all of the city I feel more at home than in Chinatown.

There is no place in all of the city I feel more out of place than in Chinatown.

If you do not understand, it is odd to hear.

(Some of you do understand; some of you will know)

Let me try to explain.

You walk through the street and the voices you hear are familiar, but they are always just out of reach, always talking too fast for you to understand.

You walk through the stores and the items are familiar, but when you smile, someone asks your companion why you are here. You only understand their response, only the words 她的 妈妈.

On one hand, this is what you know – these are the voices you grew up with, these are the foods you eat, the smells you know, the colors, the tastes, the sounds.

On the other hand – without your mother to guide you, you will always be lost.

My mother calls me. She’s sorry, she says, that she didn’t remind us what day it was before this morning. I’m at a restaurant, I tell her. Celebrating.

It had slipped her mind, she says. Since we are not in the house anymore.

(We used to light lanterns; I can’t remember the last time we did)

中秋快乐 she says.

Say it again, slowly, I tell her.

She does. Once. Twice. I repeat it, trying to get each syllable right on my tongue.

I can’t remember what it sounds like now.

I go to the grocery store on a mission. I want to find lanterns. I want to find mooncakes. If I have time, I want to find dumpling skins and bottles of yogurt drink and tins of chocolate powder.

I stare too long at the mooncakes, trying to figure out which kind is the one I like. I stare too long at the noodles and the rice, trying to figure out where the dumpling skins are hidden. I stare too long at the labels, trying to figure out which ones will evoke a deep childhood memory.

A woman asks me if I need help finding something, as if I don’t know what I’m looking for. (I do need help; I won’t admit it)

There is a full moon tonight. There were no lanterns in the store, but I bought a tin of mooncakes. I spent too much money on them, probably. But I cut one with the plastic knife, into half, into quarters, and pluck a slice between two fingers and take slow bites. It is always dense, always sticks in your mouth, always sweet.

(I do not light a lantern; I am still finding my way home)

by Quinn Hsu

i. a girl you see right through

she’s full of holes. you see her and you see right through her. look close enough and you’ll see how her insides work.

watch as she swallows shards of mirrors. watch as the shards shred her insides. watch as your own face reflects back from them even as she is ripped apart.

she doesn’t know how to sew, but still she stitches everything together. badly, and she knows she couldn’t fix it all. even so, sometimes she doesn’t know what she’s missing.

ii. a boy you can’t ignore

he still doesn’t know how to sew, but once he stitched himself together. badly, and he still doesn’t know what he’s missing. you can still see the holes through him, too.

look at the mirrors still embedded in his insides. look how he’s learned to live with the pain. but look: it’s his face you see now when you peer into the mirrors.

when you saw her, he was the one you saw right through. he’s been with her all this time. he was her, she was him.

iii. a truth you can’t swallow

sometimes you think about the filth filling the spaces between his ribs. the sediment of his experiences weighing him down. how he starts to feel so polluted and maybe he thinks it’s his own damn fault.

other times you think of the silt of his tears accumulating deep in his veins. nothing pure to rid his body of the grime. how he finally finds himself in the gut twisting pain of her mirrors.

but at what cost? his mind is a broken record player, scratching at his memories. what can he do to move on but change the record – yet any attempts to change the record would only be a bastardization of the truth.

by Angela Huang

“She looks just like you!”

My father and I have the same eyes. They are large and double-lidded, a sign of beauty in Asian culture. My father claps me on the back. I look away.

My father picks his nose while he drives. He picks his nose chronically, but there are usually more square feet be- tween us so that I can ignore it. I picked up the habit when I was younger, before training myself not to.

“Don’t pick your nose,” I say in Chinese.

His right hand, the nose-picking one, jerks back onto the steering wheel. He keeps his eyes on the road; we’ve per- formed this routine before. We continue driving in silence.

I bring a friend home in the seventh grade. My father brings us a bowl of watermelon that he has sliced into cubes. “Hi. Okay, eat this, okay?”

His English is viscous with his Chinese accent. The “okay” is a verbal tic – a common phrase in Chinese that trans- lates poorly. My friend isn’t sure what to do with the customary offering. I seize the fruit bowl.

“Thanks, dad! We’re going to go upstairs now! Bye!”

I pull my friend away. What will happen when I take a significant other home?

My father’s teeth protrude, which causes his mouth to flare out. I inherit these teeth. I beg to get braces in the eighth grade. He tells me I am too thin. My father grew up in communist China, where eating an egg was a luxury reserved for birthdays. I announce my diet to the family. I bleach my hair blonde like the white girls I see in fashion magazines. My father doesn’t understand why I do it.

“You don’t look like my daughter anymore,” he complains.

I’ve succeeded.

“You treat me like an eight-year-old. I’m twenty now. I’ve grown up. You need to stop baby-ing me!”

I don’t speak much of my father tongue: I have the linguistic control of a Chinese kindergartener. My staccatoed Chinese monologue crescendos into English. My father lingers in the doorway.

“Speak in Chinese!”

My father doesn’t speak my native English.

“Whatever.”

“Eat more.”

My father pours more rice into my bowl. His chopsticks clang against porcelain. He chews with his mouth open. His noises reverberate within the house. I fork the food into my mouth. I make a show of eating with my mouth closed.

My father thinks I should not be a businesswoman.

“It’s too much stress. I want you to be happy, not stressed. It’s unhealthy for a woman to have too much ambition.” “Dad, that’s –,” I pull out my phone to Google Translate, “–sexist.”

“That’s an American idea. One day, when you’re older, you’ll realize.”

My father drove me thirty minutes each way to piano lessons. He disciplined my hands with a chopstick whenever I sabotaged a sonata.

My father FaceTimes me sometimes. His face overwhelms my phone screen: he is holding his phone too close to his face. I lower the volume so that the voice coming out of my earbuds isn’t deafening.

“You should be more like Annie. Annie’s Chinese is good, and she always helps her family with the chores.”

My father is lecturing me again. This is how we converse: he in Confucian nags, I in grunts. Today, the target of his sermon is my filial duty.

“Well, I’m sorry I’m not Annie.”

He asks if I am eating well. I am. He asks if I am sleeping well. At least eight hours a night. He asks if I have been exercising. Not as much as I’d like to. He clucks at me. I glance at the phone screen: four minutes and twenty sec- onds. Longer than usual.

My father takes me shopping.

“I would not buy you these clothes if you went to community college. But you are my Ivy League girl!”

He swells with pride. I swallow mine. He means it out of love, I tell myself.

“Thank you.”

I stop before leaving my father at airport security.

“Bye bye, An An (my Chinese name).” He pauses. “I love you.”

“Bye Baba. Love you too.”

My father has never told me he loves me in Chinese. He reserves the term for English. Likewise, I call him “baba,” not “dad.” They mean the same thing, anyway.

by Thanh Thai

Within these pieces, I wanted to reflect on my journey as an immigrant high schooler as opposed to my time spent as a Vietnamese middle schooler. Ultimately, I aim to communicate that despite these two versions of me are “worlds apart,” in a way, I’m still a young girl who meanders in the bustling city of Saigon, armed with a bike that is slightly too big for me. And my heritage, despite being far away from my motherland, is an intrinsic quality to my identity.

I chose the moment that I asked my mom why I didn’t have a Korean name like my other Korean friends and family. This was a very important moment for me because it was kind of the start of me being affected by others around me telling me that I was different. I chose to portray this moment as more of a happy memory though, because I was able get a little closer to the person I felt I was when I received my Korean name that night.

by Danielle Du

A reflection on the impossible-possible things we are, as the walking legacy of our ancestors.

【零】

This is how it feels:

a foot in both doors,

so the saying goes—

but no one never warned you

and never did you imagine

that these doors stand

as shorelines on opposite ends

of the very

earth

you walk

(poles in their own right: north, south

no;

east, west)

—and you, the

ocean

between them:

a paradox inherent,

only ever close enough to

touch either shore,

(a body of water by grace only)

churning with the runoff

tears of both.

What are you then?

impossible

【一】

This is how it feels:

The first time you step

through that east pole door,

this is the world you glimpse:

graveyards, tombstones

filling the spaces between

these arcing highways and skyscraping towers—

death, between every breath life takes

past, between every step present makes

and neither, neither feel like yours

It feels wrong:

the ocean turns.

“Pay your respects,” your parents insist,

“Say hello to your great-grandparents.”

But you do not know them,

never knew them,

never will know them

and these headstones gleam too smooth;

so you refuse, and watch

as your parents bow in front of

this one tomb in a forest of tombs.

(a world of blood and lives and family

you have never, never known)

“Just try it,” they say, standing now,

one final beseeching lifeline:

“there’s nothing to be scared of.

It’s just three bows, then you’re done.”

But there is more than one kind of fear

that scorches this ocean floor—

you turn away,

fix your eyes to the

sky instead;

only half wondering if your great-grandparents

(and their grandparents, and their parents, and theirs,

and theirs and theirs and theirs)

can see

you,

this paradox child of two shores

torn.

【二】

This is how it feels:

How deeply you mourn that now,

enough to quench the heedless flames

that once roared through your own heart.

You know now,

now

you would kowtow a thousand times

to seize this lifeline

that, at least,

means one shore is willing

to claim you as its own.

the ocean, the ocean, ah

how it cries, longing for just one land to call

home

【三】

This is how it feels:

Even the sight of a clothes tag

makes you hear the voices

of your ancestors’ ghosts

whispering at the edges of your jacket,

snagging winter branches for hands

unerringly certain in

their own inquiry,

nonetheless afraid of your answer:

Did you forget us?

Don’t forget to remember us, now

(“made in _________,”

after all)

The cloth flaps in the breeze

of your ancestors’ rearing sorrow—

each crease and fold a sculpture

breathing,

the living image of your own regret.

You can’t help but think:

this is the real tombstone

marking that final death of memory and myth.

and oh,

how the ocean weeps

【四】

But.

This is also how it feels:

The next time you step

through that east pole door,

bearing the rains of years gone by

(years enough for

this ocean

to calm, to settle, to fill)

you watch as the quiltwork fields and glass-sleek towers

roll past, reflected to a watery blur

against the window of

your own wide-eyed longing.

Exist, exist,

you hear your ancestors cry

in this wind that pulls even the

heavens westward

as you stand, stature straightened to bow again,

returned once more:

back to this soil of your grandparents’ parents’ bones.

You wonder if they are proud:

if you have done well

at being this impossible thing—

you,

their paradox child of two shores

both.

The ghosts of your ancestors

whisper at the edges of your jacket,

drifting spring petals for hands

unerringly certain in

their own inquiry,

nonetheless awaiting your answer:

We are not forgotten, because

you still stand strong,

child of ours:

somehow, you do. Somehow, somehow,

despite it all

between it all—

and is that not the most we can ask?

You can’t help but think:

this is the first lifeline,

(and you can’t help but hope:

the first of many more)

pulling you back towards

this neglected eastern shore.

(And somehow then, you realize:

the ocean

is so, so

still.)

【五】

In the end,

this is how it feels:

Two shores,

rising on opposite ends of

the very

earth

you walk

(poles in their own right)

and you, the glittering surging

ocean

between them, somehow

holding shorelines both:

a

bridge

inherent

(between two ends

of this earth you walk,

poles in their own right:

east, west, east, west)

ever turning, yearning, astorm, aflame

ever calming, settling, stilling at last

paradoxical perhaps

impossible perhaps

This is how it feels:

still nonetheless

standing

(still, still)

between it all.

Endnotes:

by Ryan Phung

me and my mom, 3 acts

what is your nest made of

Friday was always the worst day of the week in middle school, since the library closed early and I had to sit at the curb of the empty parking lot for an hour, waiting for someone to pick me up. During winter trimester I probably looked homeless to any passerby, with the sky being a pale shade of black at only 6 P.M. and the only light shining on me coming from a single orange streetlight. I hated her. I hated how I always had to lie to my concerned friends that she would come in just a few minutes, how I had to sit in anticipation of a familiar pair of headlights, continuously on edge about the menacing stranger that would rest on a bench a few yards from me, how she wouldn’t leave her job early to pick me up as the rest of the library kids were leaving. I hated how alone I was in that parking lot, how neglected I felt, and how cold it illogically seemed on the outskirts of L.A.

It was only an hour, though.

is it grass, twigs, leaves? perhaps phở noodles, or bits of apple pie

The first step in solving a problem is to identify the issues. For years, I didn’t. I knew that I was miserable in that house, but never bothered searching for the source, mindlessly gliding on the frigid wind. I weakly accepted that she wouldn’t be the confidante for my emotional troubles, without realizing that I could at least urge her to try. So it was a glacial burn, the descent into dysfunction. Maybe I could have salvaged our relationship if I had gained clarity sooner. But why should a kid be the one to hold a family together? Where was her clarity?

The second step in solving a problem is to…

it could be crumbling mahogany brick, sturdy american steel, or even pure gold

Ignorance kept me spiteful. But even now, with the window right beside me and the clear sky outside, the ability to forgive is a virtue I don’t possess. Instead, I constantly reflect on the person I could have been. A person confident enough to start conversations with people instead of nervously waiting for someone to talk to him, who looks in the mirror and sees someone that wide-eyed middle schooler would look up to, who knows how to say sorry—he learned that from her. A person I’m not, yet one that I keep fixating on. Why?

whatever it is

If I forget the fire, would that make me him? If I pretend we were the perfect family of a Norman Rockwell painting, would that make me him? Even if I wanted to, I’ve dwelled on the dark for so long that I’ve forgotten so many of the bright memories. So how, then, will I remember her? What will her legacy be? Who is she?

it has always been your choice

Best for me, best for her.

We were on the way to band practice, me sitting shotgun in her Toyota SUV, when she suddenly asked me what career I wanted to pursue in the future. I responded with the “I don’t know” of any normal 16-year old. She then told me that she wanted me to support her financially later on in life; she even had the figure: $2000 a month. I kind of chuckled, unsure of whether this was some rare joke of hers, until I glanced over and saw a look of restrained apprehension in her dark, baggy eyes. The rest of the car ride was silent.

I didn’t think much of that incident until maybe a week later, when I noticed that she wasn’t yelling at me for things that she normally would, like playing video games for a few minutes which she assumed had actually been six hours, or not finishing a dinner plate to the very last rice pellet. At that point it slapped me across the face, a feeling that shouldn’t have felt so foreign. My future was determined, by forces out of my control. Choice was stripped from me.

I didn’t know then what I wanted to do in life, nor do I know now, but I knew what I couldn’t do. I couldn’t be a novelist. I couldn’t be a playwright. I couldn’t be a film director. I couldn’t book a flight to New York and subsist on the raw creative energy of the city like some white girl in a rom-com. Not unless I wanted my parents to suffer working their 9-5’s for the rest of eternity. Not unless I threw away every last shred of my legacy and became reborn as some lost, heartless, plucked phoenix. So I was chained, wings not clipped but shattered, because “family matters.” She fed me, changed me, housed me for years, dealt with my horrendous mistreatment of my elders, worked tirelessly year-round to ensure that I had a nice bed and a nice computer and nice clothes, poured all her hard-earned money into me, for me, because of me. Me. Everything I had was from her generous, loving hands. Far too generous for a wild beast like me. Everything she did was the best for me, everything she did was for my sake, so of course she should get a return on her investment.

Best for me, best for her.

Maybe it would have been easier to swallow if I hadn’t grown up on the pristine ideal of the white, middle-class family, of parents that raise their children with an idea of love that involves affection or anything that remotely resembles positive reinforcement, of parents that would watch bittersweetly from their freshly-trimmed lawn as their son slowly reverses out of the driveway in his newly inherited beat-up sedan, with the dad’s arm wrapped around the mom as she leans her head on his shoulder, all while some cheesy uplifting music is playing like the end of The Breakfast Club.

But I had grown up on that. They hadn’t.

Maybe she wasn’t a bad mother, just not the one I envisioned, rather one that treated affection as a luxury to be saved for a special occasion like a bottle of expensive Chardonnay. Sometimes I wonder if I was mad at her, or the fact that she worked her fingers to the marrow six days a week and barely made enough money to support her family, the fact that this was the best the supposedly greatest country in the world could muster for a poor immigrant reaching towards The Dream™. She cared about me, I think, so that’s already better than some mothers out there. But the notion that Asian love is simply a different kind of love, one that says “I love you” in a myriad of different, silent ways is utter bullshit. Looking back and realizing that she had been telling me she loved me all my life in ways I didn’t understand does not undo the trauma. At the very most, it makes the idea of shelling out $2,000 a month for the rest of her life slightly easier to stomach. A verbal “I love you” once in a while might’ve been enough to save me from years of teenage dejection, because even if I needed it not to at the time, family matters. And there’s nothing good that can come out of not knowing your family cares about you.

I wish that at some point throughout all the clashes, throughout all the screaming and misunderstandings and crying, we just sat down and talked. Maybe we would have both realized that we weren’t who the other wanted us to be, and maybe we could have both changed for the better.

Best for me, best for her.

Every Sunday at 9 P.M., my phone lights up with a notification, “CALL PARENTS.” Often I’ll ignore it, too exhausted to deal with any scolding or interrogating. The times I do find the willpower to call her, I quiver, as if the possibility of yet another verbal brawl transforms me into a recovering alcoholic. Whenever she picks up, there is, without fail, that one question.

“Why don’t you want to come back home?”

To say she cried when I moved into my college dorm would be an understatement. Tears were streaming down her face when we got in the car, and they were pouring even harder when we arrived. By the time we had finished unpacking and I was trying to free myself from her grasp to explore my new world, she was a sobbing mess. Even a few hours later when she got back and fully registered her nest as empty, she was still crying, at least according to our brief phone conversation when she reminded me yet again to call every week. My face was dry.

I thought I would feel electrified about the prospect of living without the constant fear of her barging into my room and berating me for some meaningless atrocity I committed. Yet as I laid on my new mattress, staring at a new white stucco wall, it seemed like I was still caged in that decrepit house.

Her home always felt foreign to me, even though I spent by far the most time there out of anyone in our family. Her home was the stronghold of my most cherished memories, like drowning out their aimless arguments with video games and music, or the blaring silence of yet another afternoon with no one to greet me at the door. Her home was small, far too small to hold my soaring dreams and starry-eyed fantasies. Her home was a perpetual reminder of a childhood gone to waste, of teenage years wrought with frustration and uncertainty, of two adulthoods with nothing but endless toil and weary hope. Her home was everything she had worked for, so I could lead a far better life than she would ever be able to, yet it wasn’t enough.

Her home never felt like mine. I’m not sure any place has.

Forgive and forget. It’s probably easier to do when your little brother cries and frames you for physical assault, or when your friend “accidentally” tells your crush that you like her. But how do you even begin to forgive someone who molded you into a mess of a person, someone who shattered your wings and ordered you to fly? Despite how many times I’ve tried to console myself, “She tried her best. She couldn’t be there for you, but she tried her best,” the bitterness always remains. Even when we’re on good terms, it still feels as though so much is missing, as though the stars and planets could have formed between us. Part of me always wants to push her away, as if to remind her that I molted into a decent person not simply without her, but in spite of her. But I always come back, for I grew up because of her.

No matter how much I may covet that pristine white ideal, I cannot and should not forget the helpless hours. But I should pretend I can, for her sake. The journey to the person I am today was not a ship smoothly sailing off from the harbor, but neither was hers. Every single time she and I fought, it killed her just as painfully as it did me. She suffered, in her aching bones, her baggy eyes, her tired spirit. She knows she was far from perfect, and she’s trying desperately to make up for that now. I have to at least let her try. Maybe as the clock ticks by, we can begin to balance the dark memories with new, pleasant ones, picking up the forgotten and reimagining the old along the way.

I want to come home, but first I have to find it. For now, I wait by the window, gazing out at the open sky from a nest of pale-green jade, by my own choice.

It has always been my choice.