VOICE OF THE DETAINED

What are our alternatives to conduct an oral history with detained people?

This project was conducted for the Race and Oral History Course at UCSD in the Spring of 2019. This post is a reflection on the limits of oral history and ways to overcome them through an engagement with the letter. The letter I chose was written by a Mexican mother to Detainee Allies.. She is 37 years and had been living in San Diego for 19 years before being detained. In this post, you will find a reflection on how to rethink oral history thanks to an artifact. I will provide a personal analysis of the letter, highlighting sections that articulate the following themes: endless violence, militarized border, family, vulnerability and confinement. The goal of this project is to amplify the voice of one detainee confined at Otay Mesa Detention Center. Closed from the outside world and deprived of face-to-face interactions, detainees have resorted to letter writing to speak out and to convey their humanity. Reading their letters creates a form of encounter that approximates an oral history interview.

How does one do oral history with someone who is detained? In what ways can letter writing constitute an act of refusal of the government’s mandate of isolating human beings from the social world beyond the walls of the detention center?

Detainee Allies is a grassroot organization that uses letters to connect with people held captive at the Otay Mesa Detention Center. Its aim is to amplify refugee voices through letters. What I find beautiful about Detainee Allies is that they are putting the human at the center at a time when our government is dehumanizing migrants and asylum seekers, and criminalizing them. Against this dehumanization, Detainee Allies is creating social relationships between human beings. Thus, for this project, I decided to use the knowledge and values learnt during my weekly meeting with Detainee Allies. Even if face-to-face contact with the people detained is impossible, letters make it possible to hear their stories. In these letters, refugees share their life journeys and the deplorable conditions of the detention center. Letter writing is an intimate social practice. The letter is a powerful and compelling testament to one’s humanity. According to Sharon Luk, the letter is a work of art, the weight of its significance goes beyond the literal words inscribed on the page.

I focus on one letter written by a Mexican detainee. She is a 37-year-old woman who has lived in the United States for 19 years and in San Diego since 2003. She has been detained at Otay Mesa Detention Center since 2017. The letter was written in August 2018. Considering this piece of correspondence as a work of art allowed me to go beyond what was first literally said in the letter. I engaged with its content as well as its format, offering my own interpretations while highlighting her voice. It is a collective work between me and the detainee.

The aim of oral history is to give voice to people who have been written out of history, to amplify their voices. Although this letter was not written with an activist aim, I am adding to this letter a political aspect and giving it a new meaning. This letter is both a personal message and a political statement. It is a testament to the humanity of migrants.

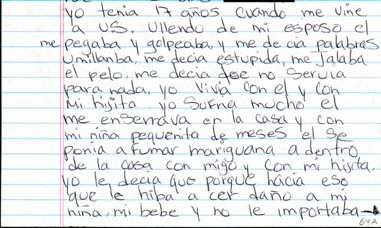

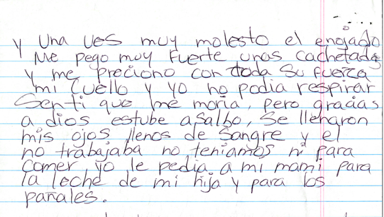

ENDLESS VIOLENCE

She explains the reason why she left her country. She describes in great detail how her husband brutalized her and her daughter. She was scared for her life and the life of her daughter. Once, she even believed he was going to end her life. So she decided to leave. Her decision to come to the United States was motivated by her desire to protect her family from violence. But she could not escape the violence, as she merely left one violent situation for another. Domestic violence was followed by state violence in the Detention Center (cf: section five). Women refugees are also vulnerable to gender-based violence inside detention centers and at the border at the hands of state agents. While they are fleeing an unbearable violent situation in their home, town or/and country, they are often encountering a situation even more embedded in violence in the country they considered as a safe place.

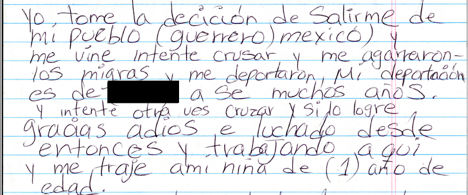

MILITARIZED BORDERS

Following her description of her life in Mexico, she gives details of her multiple attempts to cross the Mexican/US border. She explains that she has been deported once while she was trying to enter the United States. She has never stopped trying to reach the “safe haven”.

This section raises another question of how the United States deals with “their refugee crisis”: Does the deportation strategy make sense? The state violence at the border is aimed at breaking the hopes and even the physical bodies of refugees, and to dissuade them from crossing again. However, people who fled their countries in search of safety won’t stop at the Mexican/US border. They will try to cross by any means. The decision to cross is not a spontaneous one. For this woman, crossing was a means to protect her body and the future of her daughter.

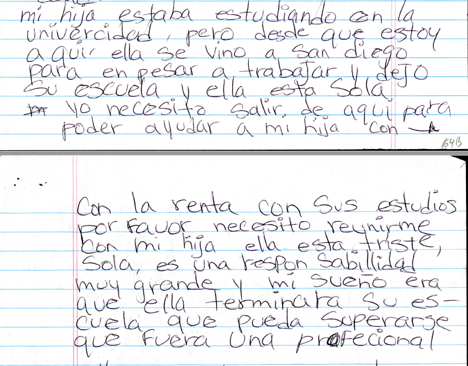

FAMILY

In the United States, she tried to rebuild her family far from the violent household she has experienced. Her daughter entered university. But everything changed since she has been detained. Her daughter stopped her studies and moved to San Diego to start working and to earn money. She wishes for her daughter to finish school. She came to the United States to give a better future to her daughter, and education is one of the key.

This section highlights that detainees often are not alone and that they have people who are dependent on their care. The lives of their family are also disrupted and put into crisis. The detention of one person breaks apart families, communities, and their whole ecosystem.

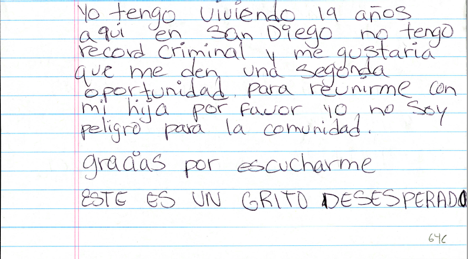

VULNERABILITY

This section is about being human and making one’s humanity legible. This woman’s vulnerability is underlined in this section. What strikes me in this part is the obligation to adopt the language of the state to be considered “innocent.” She is responding to the state’s language of fear point by point. She has to prove to “a foreign community” that she has enough value as a human being. She needs to make her existence legitimate to the audience.

“ESTE ES UN GRITO DESESPERADO”. The last sentence of this section helps us to understand why writing letters is so compelling and important. The words are picked carefully. Her handwriting allows her to stress some parts. It is written in capital letters and placed in the middle, and it seems the writer struggled to write the last word. This point brings us to think about the practice of letter writing. Communication is a basic human need. Building relationships through letters and communicating stories is one way to keep one’s humanity when that humanity is denied through confinement. Communication is an intrinsic need but also is a form of resistance. In this case, writing is both painful and liberatory. The story told is not an easy one to share. However, this practice can be seen as a tool to heal inner-wounds.

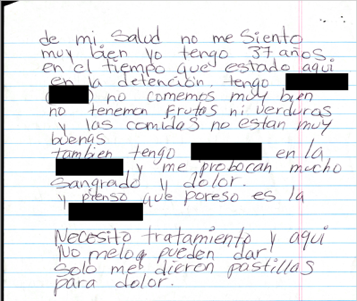

DETENTION

In this last passage she switches her role. She no longer speaks solely as a woman and a mother but also as a detainee. In this letter, we can notice that the author of the letter is writing under multiple roles: she is a woman but also a mom and now a detainee.

She explains the conditions in the detention center and the deprivations: restricted access to food, no vegetable or fruits, medical neglect. The violence of detention is both physical and psychological. It brings us back to the question: What does it mean to be human? Is it the mere fact of being alive? What does it mean to leave human beings in conditions of minimal existence? As A. Naomi Paik argues, the state enacts its power on detainees by keeping them in a state of limbo between living and dying.

To conclude, reading this letter creates a form of encounter between us and the detained Mexican mother that is foreclosed by the state. Letter writing is at once personal and political.