In our group (Marné Amoguis, Aaron Ngan, and Ryan Okazaki), there were two parts of our project: our community projects and our final art presentation. Both share relevant themes in mental health and Filipino American identity. Due to the timing of our partnership with the Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS), we decided to focus our projects on the intersection of mental health and identity. Considering that May is both Asian/Pacific Islander American Heritage Month and Mental Health Awareness Month, it was only fitting. In order to raise awareness about these topics, we decided to participate in various presentations to our fellow students and community members. We collaborated with Judy Patacsil, our contact with FANHS and also a Professor of Filipino Studies and the Coordinator for Mental Health Counseling at Miramar College, to organize three events related to API identity and mental health.

Our first event was on May 13. This was a presentation from Amanda Lee, LCSW. She taught students at Miramar College the different ways that mental health differs in various communities — particularly in the API and LGBTQ communities. The presentation was a straightforward introductory overview to mental health problems, specifically stress, depression, and the role that identity and community play into mental wellness. and involved a fun icebreaker activity: tossing around a beach ball and talking about different coping methods, sources of stress, and various parts around an individual’s identity.

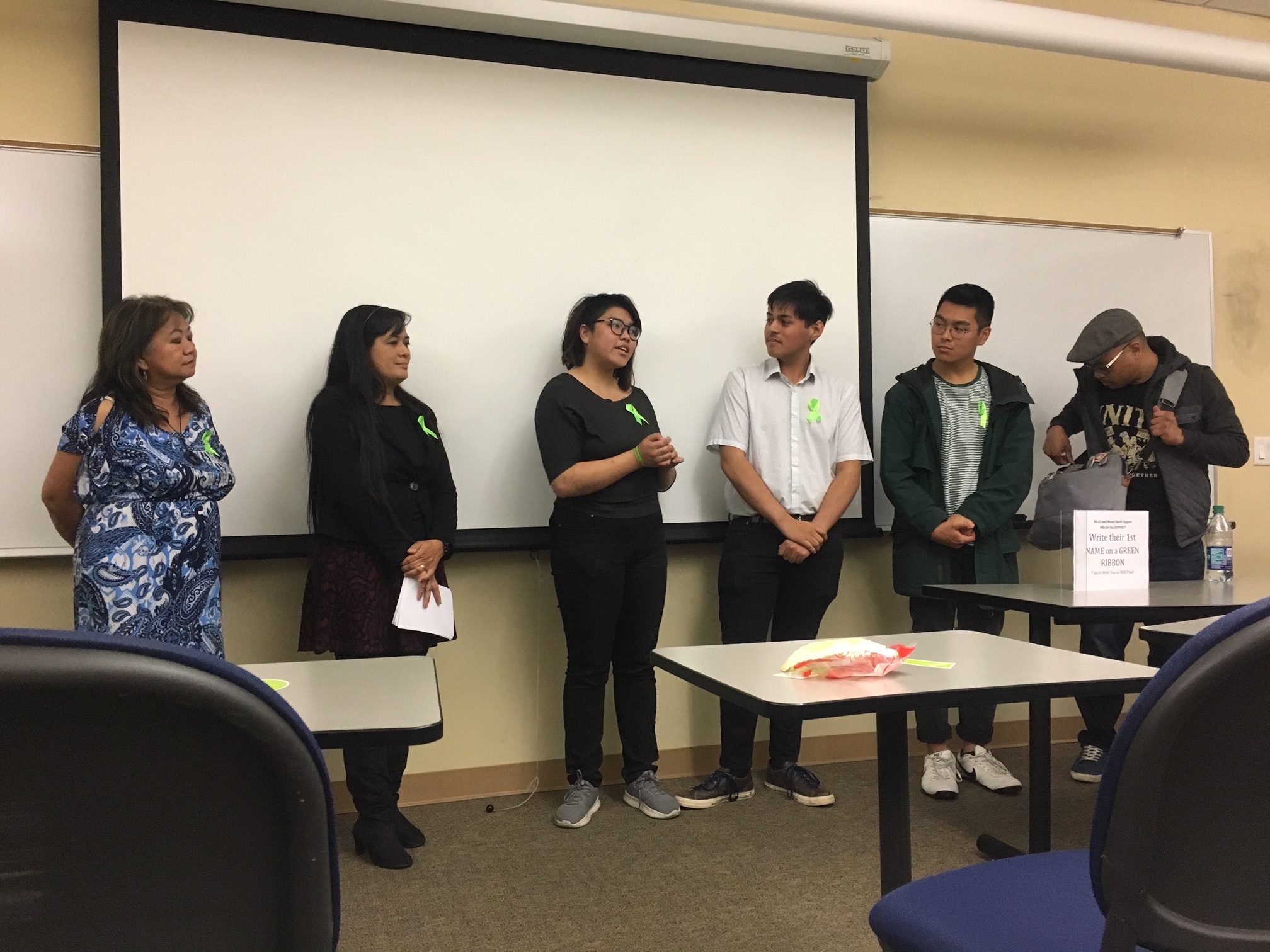

Our second event was a few days later, on May 16. This was another presentation to students, but this time, it was for students, by students. Our group went to Grossmont College in order to speak to students about microaggressions in the API community. There, we were joined by two other students, both from local community colleges. The process of creating the questions for the panel and actually participating was a learning experience for each member in our group because we realized the ways in which microaggressions have affected our own lives. Once we conducted the panel, we realized that the stories we told were quite intimate in such a public setting. The reaction of the audience caught all of us off guard because of the honesty and openness they showed after we finished speaking on the panel. When the questions were opened to the audience, we heard about belittling experiences with autism to the fears of racial profiling. Most were stories that, had we not told our own, would not have been heard. In that space we developed an overwhelming sense of community solidarity and respect for one another. By the end of the event, when everybody started walking out of the room, people approached us to thank us for sharing our stories and letting them share theirs. The openness of the audience taught us panelists just as much as our stories taught them.

Our final event was on May 17. Unlike the other two, this event was geared towards local community members. At Miramar College, we showed the film Silent Sacrifices: Voices of the Filipino American Family and followed up with a group discussion. Silent Sacrifices is a 26-minute documentary with interviews of Filipino Americans in San Diego on the topics of culture, family, and mental health. The film was created in response to a report by the Center for Disease Control which showed that Filipino Americans, and Filipina women in particular, thought of suicide at higher rates than any other ethnic subgroup. By creating a film such as Silent Sacrifices, community members sought to normalize the difficult conversations around microaggressions and mental health in Filipino American families. For example, one of the fathers in the documentary discussed how he regretted not saying “I love you” more to his children as they were growing up. Some of the youth discussed growing up Filipino American but not really knowing what that meant. There are certain differences between Filipino culture and American culture that were confusing, such as the concept of Filipino time or feeling not Filipino or American enough. There were about 30 people who attended the film screening. Those who spoke in the group discussion afterwards resonated with many of the themes and experiences in the documentary, and we were grateful to have led such important and impactful community conversations.

Because of everything we learned, we were inspired to have our art project reflect these ideas of how storytelling and fragmented memory can have an impact on one’s mental health and wellbeing. With our experiences during these events, we came to learn how by sharing one’s story, they are able to solve internal conflict, while also presenting greater truths in life. In honor of this, we have decided to offer a space for people to share their own stories about identity and mental health. And not only that, the entire class is structured around ways in which telling stories has the power to benefit a community, where individual voices are elevated against traditional historical methods of archiving the voices of the powerful and influential. Storytelling enables communities to begin healing processes. Whether about unraveling the mysteries of one’s own culture, enumerating the hardships of daily life or tackling issues of conflict and belonging, stories best represent the human experience. Because of this, our final art project for the community showcase brings together a collage of memories of people in the San Diego community. Through hanging photographs, drawings and their descriptions onto a frame that will be decorated with the colors of the Filipino flag, the memories of our work with FANHS will be displayed; however, because the process of storytelling and memory recollection can oftentimes be a mess, we are encouraging all the attendees of the community showcase at the East African Cultural and Community Center to contribute drawings and descriptions of memories they would like to share. This culminates in a great “mess of memories” to showcase not only the work that our group has done with FANHS but the diversity and creativity of the larger community the Race and Oral History Project has engaged with.

The ability to share your stories is a privilege that nor everyone if fortunate to have. But by normalizing this experience and generating such conversations, we can all work towards a future where mental health loses its stigma. That is the ultimate goal of our project. By first sharing our stories and the stories of the community around us, we are able to start necessary conversations and dialogues that would not have happened otherwise.