I would like to pay my respects to the Boon Wurrung (Bunurong) People, Traditional Custodians of the lands I reside and work, and pay my respects to their Elders past, present and emerging. I extend these respects to any Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people reading this.

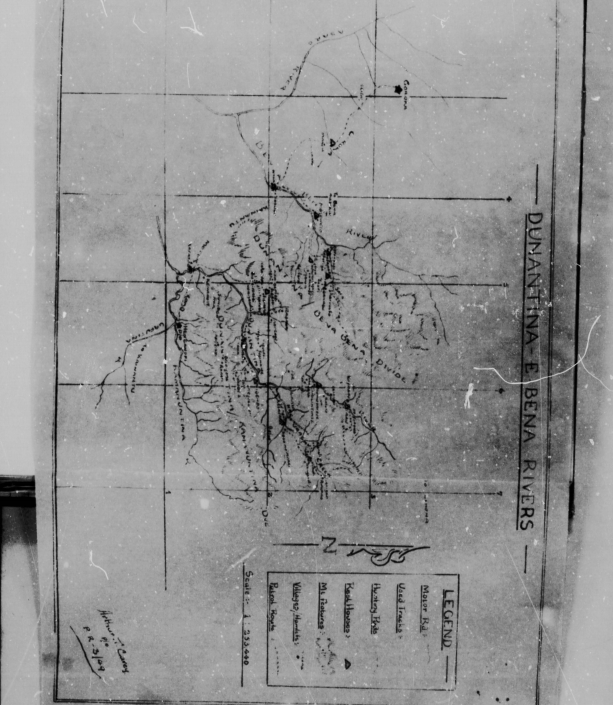

Arthur T. Carey’s patrol report from 26th October to 16th November 1949 saw Carey accompanied by four ‘native’ policemen: a Lieutenant-Corporal and three Constables.[1] ‘Unfortunately, no Medical Orderly was available to accompany the Patrol.’[2] The reasons for this are unclear, but it could be because it was a relatively early patrol where the ‘doctor ratio [was]…about 1 for 10,000 people.’[3] Carey made no mention of local carriers, so, was the patrol short enough not to require them, or were they simply not worth mentioning? Carey’s praise of his police companions makes the latter seem unlikely. The purpose of this patrol was for ‘assessing census figures…routine administrati[on]… and the replotting of village positions on the map’ – see appendix two.[4] Along the patrol, they also conducted minor medical examinations and reported any damage they encountered, ensuring that locals knew how to prevent damage in the future. Throughout this essay the role of the Patrol Officers, and the importance of their tasks will be explored. Carey settled a bride-wealth dispute, a practice that was beginning to change with the introduction of Western ideas. Traditions were altered by the introduction of capitalism and ideas imported from white patrol officers, missionaries, and Indigenous people returning from working the Lowlands, via the Highlands Labour Scheme. Traditional customs, like polygamy, were restructured as inherently wrong through the introduction of Western religion. Were the so-called advancements welcome or merely imposed on people who already had their own system? Colonialism so often leads to the assimilation of traditional practices. Did Papua New Guineans manage to maintain some traditions, or were they all overthrown and remodelled under the Western Eye?

Patrol officers, who were white men, were known by many aliases. Some examples include: ‘kiap, taubada, gavamani, out-side man, big-man, big boss, cadet patrol officer, and literally hundreds of other names.’[5] These men held a lot of power over the regions and people they were patrolling. When the exploration of the Highlands began, there was inevitable fear from both sides. As such, patrol officers would use their guns to establish control and dominance. This was done to show how an arrow, shield, or even a pig could not survive a bullet. However, Hubert Murray eventually put in place a ban on ‘shooting to punish,’ and, as such, a ‘tradition of restraint developed.’[6] Was this ‘tradition’ what led to the friendly interactions between ‘natives’ and the representatives of the colony?

Following the Great Depression in Australia, the demand for patrol officers went down as more and more young men were applying. As such, the entry requirements increased, with learning Tok Pisin and Motu becoming prerequisites. Following the Second World War, these requirements again were amplified, with potential recruits being required to receive ‘instruction in colonial administration, anthropology, law and order in Papua-New Guinea, practical administration, elementary medicine, tropical agriculture, geography, scientific method, Tok Pisin and Motu, animal husbandry and entomology, and the machinery of administration and administrative policy in New Guinea.’[7] This deeper insight and understanding into Papua New Guinea and its people could very well have helped pave the way to friendly understanding and cooperation between Indigenous Highlanders and white officers.

Western ideals and religion accompanied patrol officers and missionaries, and fear was often implemented as a conversion tool. Carey’s mission to Dunantina and the Bena River saw a ‘particularly strong’ mission influence from the Lutheran church, which was one of many missionary groups present throughout Papua New Guinea.[8] Papua New Guinea became the arms race of the religious world. The Lutheran church had realised the best and most efficient way of spreading word – through the education and ‘special use of the black evangelists.’[9] Though, simply because Indigenous people were being utilised, did not mean that traditional practices were given the go ahead. An example of this, as noted in Carey’s patrol report, was the ‘fatal sin of committing polygamy.’[10] Polygamy, the practice of taking multiple wives, was common throughout Papua New Guinea, where one was even recorded as having seventeen![11] In order to be baptised, and thus be able to ascend to heaven upon death, ‘where all the pigs… kina shells…and all the good things of life are,’ one must adhere to the regulations of their religion.[12] Many men got rid of their ‘extra’ wives, with one even ‘kill[ing] two off.’[13] However, according to Carey this was, in his ‘considered opinion,’ ‘fundamentally wrong,’ and as such, monogamy and baptism should be ‘left to the younger generation.’[14]

On this note of marriage, along his patrol, Carey was called upon to assist on a disagreement of bride-wealth, which he managed to ‘amicably settle.’[15] With a practice as traditional as bride-wealth, it seems odd that Indigenous people would call upon their white colonisers to weigh in. With the great power the Kiaps held, they were often required to be judge, jury, and officer, and whilst the local Elders were the traditional power holders, colonialism had undermined this control, and as such many looked to the patrol officers for help in settling law-related disputes.

To many western countries, bride-wealth may seem old fashioned and possessive, though, for women in Papua New Guinea, it is ‘bride-wealth that makes adult women wali ore (real woman),’ and real women are ‘defined in terms of enduring relations to others…and it is bride-wealth which establishes these enduring relations.’[16] It is incredibly easy to misjudge traditional customs as domineering and outdated, however, in reality, it has been an integral part of society, one that gives women a ‘sense of self-worth.’[17] Unfortunately, however, with the world changing and becoming a capitalist machine, the understanding and concept of bride-wealth is changing, coming to be thought of as bride-price instead, which reflects that it is ‘becoming a commoditised transaction.’[18] For obvious reasons this can be dangerous and could lead to the further denigration of women in society, where they become nothing more than a possession that has been purchased. Holly Wardlow discusses this in her book Wayward Women: Sexuality and Agency in a New Guinea Society, where she highlights an encounter whereby one woman was told ‘I paid bride-price for you and so you must do my laundry.’[19]

As Wardlow clearly states, ‘bride-price was the idiom through which husbands attempted to legitimate their authority over wives and their entitlement to wives’ services.’[20] A changing world, society, and customs could lead to the collapse of societal structures, knowledge, and practices. This could, unfortunately, lead to women losing ‘her own autonomy, dignity and respect within her husband’s group and among the people with whom she…has to rely on for support.’[21] With Highlanders leaving for work and education, and later returning home, the rate of ‘mixed marriages’ was gaining in occurrence. This led to further tensions in the settlement of bride-wealth, in that different groups have ‘very different bride-price customs,’ or where ‘bride-price is not practised’ at all.[22] Therefore, the involvement of the colonial administration, and patrol officers like Carey, was becoming increasingly necessary.

The causalities from the War resulted in an influx of work, and employers began to look at the Highlanders untapped population for new employees. Unfortunately, this led to a lot of sickness, with the most common assailant being malaria. The Highlands topography, despite Careys report of ‘constant rains,’ was not suitable for the breeding of malaria infected mosquitos, so Highlander locals had not built up a natural tolerance to malaria in the same way that people by the coast had. Where, ‘in 1935, a group of 70 people… were taken to the coastal administrative centre…after one month, 17 were returned home, but within three weeks 16 of these had died.’[23] With the demand for workers by the coast growing, and the administrators fear of Highlanders realising they could ‘just walk there themselves,’ the health director finally agreed that – provided Indigenous workers were administered tuberculosis vaccines, malaria suppressants, and were quarantined prior to returning home – they could be recruited for work.[24] Employers were not permitted to recruit themselves, and therefore, this responsibility fell on the shoulders of patrol officers, in a ‘radical innovation.’[25] Where, ‘they would not act as recruiters themselves, but would simply advise people of the possibility for and general conditions of contract work.’[26] Carey himself most likely would have played a role in this during his patrols in Goroka, as there was a ‘recruiting or “attestation” centre, located near the airfield and government station at Goroka.’[27]

This, of course, was not Carey’s only patrol. Another patrol that he was a part of, though not directly reporting it by name, saw him becoming the first to have reported ‘the earliest reference to kuru found in… archival searches.’[28] Where he ‘noted that…[people] get violent shivering’ which was ‘fairly continuous’ and then proceed to ‘die fairly rapidly.’[29] Kuru, which has now been connected to Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), was prevalent in the Highlands, predominantly in young children and women.[30] It was suggested – and later confirmed – to be linked to cannibalism, despite the fact that people, young and old, were displaying symptoms and dying of kuru ‘even 15 years after they had stopped eating their dead.’[31] Michael Alpers was determined to stay on in Papua New Guinea and not forget about it in the hopes of, instead, working to receive Nobel and medical prizes, like his colleague Carelton Gajdusek had.[32] Alpers was determined to remain and document every case of kuru, in order to have full insight into incubation periods. With the emergence of Variant CJD in England in 1985, Alpers’ prolonged study in Papua New Guinea was crucial when people who ate infected beef began displaying symptoms ten years later. Whilst a patrol report from the 1950’s may seem inconsequential, it shows how a patrol officer, anthropologist, and medical researcher can be key in gaining understanding of a new disease emerging in humans.

Clearly, patrol officers in Papua New Guinea were responsible for more than simply collecting census and reporting back on administrative bounds. Their tasks, on top of their ‘normal’ duties, extended to: policing, job advertisement, map plotting, and settlement of bride-wealth disputes. There is no doubt that patrols overworked and treated ‘native’ carriers abysmally, and the deaths of local people should have been avoided at all costs. White colonial authorities have a track record of destroying, overtaking, and forcing assimilation on Indigenous populations to recreate them in the white image. So, was there any difference in Papua New Guinea?

The Second World War saw a change in attitude toward Indigenous people of Papua New Guinea after the comradery that was built between the soldiers and the ‘fuzzy wuzzy angels.’[33] Regardless of the cause, the education, employment and health care for Indigenous Papua New Guineans was on the rise, with the hopes of, eventually, leading Papua New Guinea to Independence. ‘Despite global pressures for fast tracking PNG independence,’ Paul Hasluck stated that ‘economic development not only should, but would, come before political development.’[34] Patrol officers, soldiers, politicians, and people living in Papua New Guinea developed bonds and friendships with Indigenous people, and through this, Indigenous people were educated and encouraged to participate in local politics and economics. Due to this, Papua New Guinea were able to develop a constitution for the people, by the people, which managed to include and maintain their link to traditional kastoms, despite the colonialism they had experienced for more than a century before. As mentioned above, Carey’s lack of reference to any carriers is intriguing. In future research assignments, Arthur Carey’s other reports could be studied to gain insight into why this occurred to see if they had any mention of Indigenous carriers, or if their invisibility was a key theme across his time as a Kiap.

Overall, despite their failings, patrol officers managed to help hundreds of people across the Highlands. The development of the Australian School of Pacific Administration (ASOPA) in 1946, meant there was anthropological and colonial education provided for patrol officers. Whether this was done to better understand how to bend the wills of the ‘natives,’ or to ensure harmonious relations between Indigenous people and the Administration is a topic needing much more extensive research.

APPENDIX ONE:

200-WORD SUMMARY:

Arthur T. Carey’s patrol set out in the Eastern Highlands towards Dunantina and the Bena River on October 26th 1949, with the objective of assessing the census and undertaking routine admin. Carey was accompanied by four ‘native’ policemen whom he gave high praise for their ability on patrol. Their journey was impeded due to the poor weather brought on by the late wet season. Through their journey they inspected, counted and ‘requested the assistance of all local natives’ on caring for, and maintaining, any damaged roads or bridges.[35] Minor medical examinations were performed on the Indigenous people, but without a doctor accompanying them, it was lucky there were only a few who needed further medical assistance. These were two cases of pneumonia, which were helped with Sulpha drugs, so they could make it to hospital. Carey assisted in settling an issue on bride-wealth, and made a rough estimate on the ‘yearly birth rate figures.’[36] Despite the poor weather and incomplete census due to the movement of Indigenous people, Carey declared the patrol ‘highly successful.’[37] The villages, Village Officials and ‘natives’ were deemed ‘good,’ and the co-operation from local people was respectable. After a 22-day Patrol, Carey signed off by stating the patrol was overall ‘pleasurable and satisfactory.’[38]

APPENDIX TWO:

A. T. CAREY’S MAP

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Bygott, R., & Davis, J., & Aleprs, M., (2009) ‘Kuru: The Science and Sorcery’, Kuru: The Science and Sorcery SBS ONE, EduTv, Broadcast Date: 19 December 2010, accessed 21 September 2021.

Carey, A. T., (1949) ‘Territory of Papua and New Guinea Patrol no. 3 of 1949-50’, 26 October – 16 November, 1949, National Archives and Public Records Services of Papua New Guinea, Patrol Reports, Eastern Highlands, University of California, San Diego, https://library.ucsd.edu/dc/object/bb07526564, accessed 17 August 2021.

Henry, R., & Vavrova D, (2020) ‘Brideprice and Prejudice: An Audio-Visual Ethnography on Marriage and Modernity in Mt Hagen, Papua New Guinea’, Oceania, 90:3, accessed 19th September 2021.

Imbun, B. Y., (2016) ‘The Genesis and Performance of an Australian Wage-Fixing System in Papua New Guinea’ Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, Inc., no. 110, accessed 16th September 2021.

Inglis, K. S., (1969) ‘War, Race and Loyalty in New Guinea, 1939-1945’, The History of Melanesia: Second Waigani Seminar, vol. 30 (1969, University of Papua New Guinea; Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, Port Moresby), accessed 25th September 2021.

Kituai, A. B., (1988) ‘The Role of the Patrol Officer in Papua New Guinea’, My Gun, My Brother: The World of the Papua New Guinea Colonial Police 1920-1960, University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu, accessed 15th September 2021.

Nelson, H., (1982) ‘On Patrol’, Taim Bilong Masta: The Australian Involvement with Papua New Guinea, Australian Broadcasting Commission, Sydney, accessed 15th September 2021.

Radford, A., & Scragg, R., (2013) ‘Discovery of Kuru Revisited: How Anthropology Hindered Then Enhanced Kuru Research’, Health and History, 15:2, Australian and New Zealand Society of the History of Medicine, Inc., accessed 27th September 2021.

Scragg, R., (2010) ‘Science and Survival in Paradise’, Health and History, 12:2, accessed 22 September 2021.

Ward, R. G., (1990) ‘Contract Labor Recruitment from the Highlands of Papua New Guinea, 1950-1974, The International Migration Review, 24:2, accessed 21 September 2021.

Wardlow, H., (2006) ‘I am Not the Daughter of a Pig! The Changing Dynamics of Bridewealth’, Wayward Women: Sexuality and Agency in a New Guinea Society, University of California Press, Berkeley, accessed 28th September 2021.

[1] Arthur T. Carey, ‘Territory of Papua and New Guinea Patrol no. 3 of 1949-50’, 26 October – 16 November, 1949, National Archives and Public Records Services of Papua New Guinea, Patrol Reports, Eastern Highlands, University of California, San Diego, https://library.ucsd.edu/dc/object/bb07526564, accessed 17th August 2021.

[2] Ibid., p. 5.

[3] R. Scragg (2010) ‘Science and Survival in Paradise’, Health and History, p. 75.

[4] Carey, ‘Territory of Papua and New Guinea Patrol no. 3 of 1949-50’, p. 1.

[5] A. B., Kituai (1988) ‘The Role of the Patrol Officer in Papua New Guinea’, My Gun, My Brother: The World of the Papua New Guinea, University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu, p. 20.

[6] H., Nelson (1982) ‘On Patrol’, Taim Bilong Masta: The Australian Involvement with Papua New Guinea, (Australian Broadcasting Commission, Sydney, 1982), p. 5.

[7] Kituai ‘The Role of the Patrol Officer in Papua New Guinea’ p. 30.

[8] Carey, ‘Territory of Papua and New Guinea Patrol no. 3 of 1949-50’, 26 October – 16 November, 1949, p. 7.

[9] Nelson ‘On Patrol’, p. 1.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Carey, Territory of Papua and New Guinea Patrol no. 3 of 1949-50’, 26 October – 16 November, 1949, p. 7.

[15] Ibid., p. 3.

[16] H., Wardlow (2006) ‘I am not the daughter of a pig! The Changing Dynamics of Bridewealth’, Wayward Women: Sexuality and Agency in a New Guinea Society, (2006,University of California Press, Berkeley), p. 112.

[17] Ibid., p. 101.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid., p. 106.

[20] Ibid.

[21] R., Henry & D., Vavrova (2020) ‘Brideprice and Prejudice: An Audio-Visual Ethnography on Marriage and Modernity in Mt Hagen, Papua New Guinea’, Oceania, 90:3, p. 226.

[22] Ibid., 218.

[23] R. G., Ward (1990) ‘Contract Labor Recruitment From the Highlands of Papua New Guinea, 1950-1974, The International Migration Review, 24:2, p. 280.

[24] Ibid., p. 281.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid., p. 281-282.

[27] Ibid.

[28] A., Radford & R., Scragg (2013) ‘Discovery of Kuru Revisited: How Anthropology Hindered Then Enhanced Kuru Research’, Health and History, 15:2, Australian and New Zealand Society of the History of Medicine, Inc., p. 33.

[29] Ibid.

[30] R., Bygott & J., Davis & M., Alpers (2009) ‘Kuru: The Science and Sorcery’, Kuru: The Science and Sorcery, , SBS ONE, EduTV, Broadcast Date: 19 December 2010.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] K. S., Inglis (1969) ‘War, Race and Loyalty in New Guinea, 1939-1945’, The History of Melanesia: Papers Delviered, Second Waigani Seminar, vol. 30, University of Papua New Guinea; Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, Port Moresby, p. 503.

[34] B. Y., Imbun (2016) ‘The Genesis and Performance of an Australian Wage-Fixing System in Papua New Guinea’ Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, Inc., no. 110, p. 146.

[35] Carey, ‘Territory of Papua and New Guinea Patrol no. 3 of 1949-50’, 26 October – 16 November, 1949, p. 3.

[36] Ibid., p. 6.

[37] Ibid., p. 8.

[38] Ibid.